How did it all start?

Turbulent, exciting and full of change – these are words that best characterise life in Estonia in the 1990s.

The winds of change that began in the second half of the eighties led to the restoration of Estonia’s independence on 20 August 1991, and everything that had been forbidden for the previous half century became possible, from free speech and free elections to the freedom to be an entrepreneur.

Estkompexim opened the Penguin ice cream café in Pärnu in May 1990. The so-called Penguin ice cream is remembered by everyone who was of ice cream-eating age in the nineties. Photo: Henn Soodla / National Archives

Private enterprise was banned in the Soviet Union, and it was only in 1985, when Mikhail Gorbachev became the leader of the Soviet Union, which is to say the General Secretary of the Communist Party, that the oxygen taps were opened a little more. This also meant moving away from the socialist command economy, which had caused, among other bad things, a chronic shortage of goods on 1/6th of the planet, and heading towards a market economy.

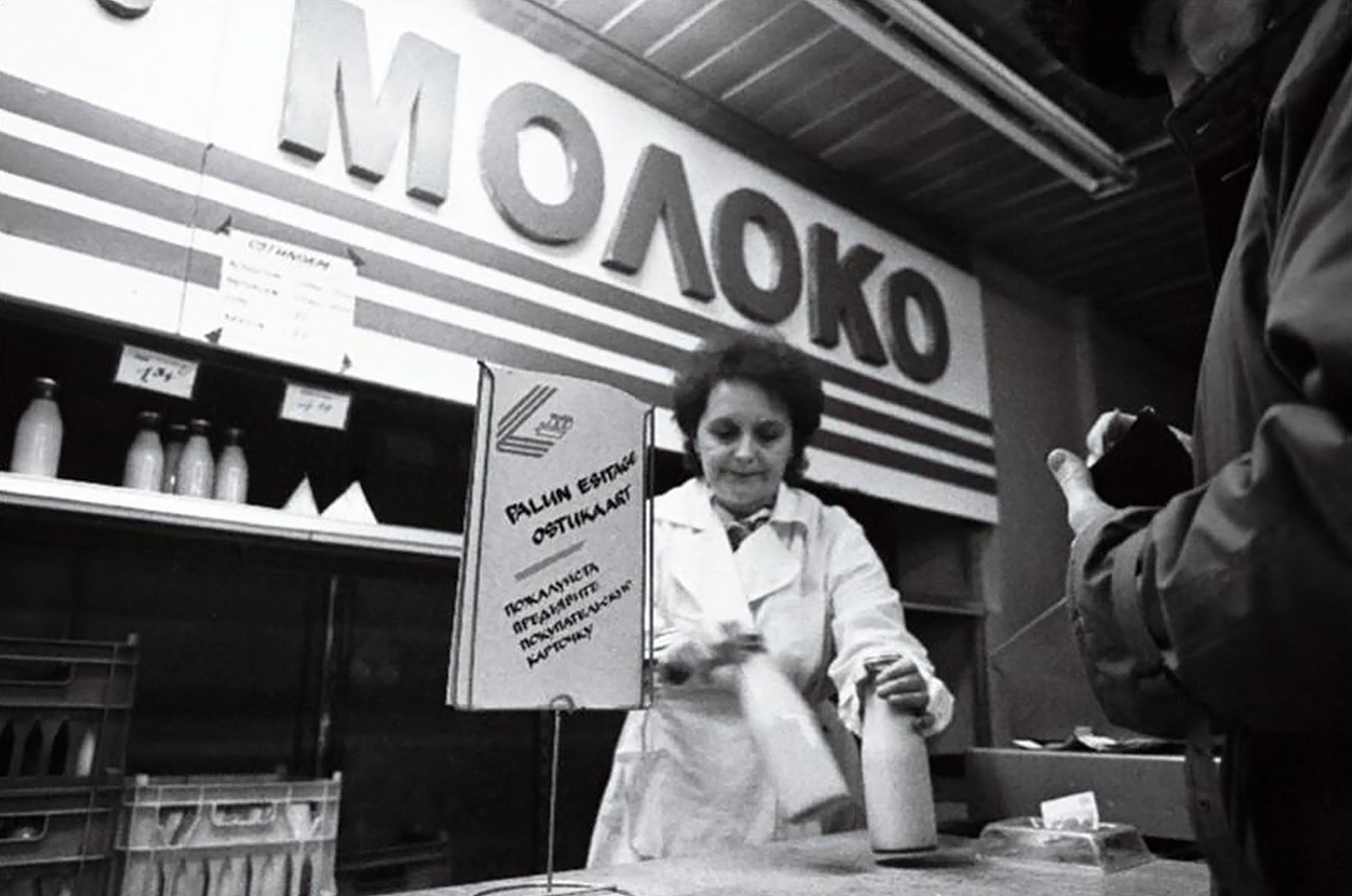

Purchase cards were introduced in Estonia in 1990 to protect the domestic market from shoppers from elsewhere in the Soviet Union. For example, you needed the card to buy milk. This photo is of the ‘Leningrad’ store in Lasnamäe, Tallinn. Photo: ETA/National Archives.

In Estonia, 1987 can be considered the rebirth of the market economy, as a decree was passed in the Soviet Union that allowed the establishment of joint ventures with foreign partners and the establishment of small enterprises, or cooperatives. Admittedly, some restrictions were initially in place: cooperatives could only operate as part of state-owned enterprises or institutions.

The renewed freedom to do business can undoubtedly be counted among the positive changes in society, but at the same time there were many negatives. Crime was rife, and businesses were sometimes preyed on by racketeers offering the ‘service’ of guaranteeing safe business operations in return for money or other benefits. The economy was on the verge of collapse and the deficit of goods was worsening, so in January 1992 an economic emergency was declared in Estonia and basic foodstuffs such as milk, bread and butter had to be bought using coupons. The value of the rouble plummeted and inflation reached over 1000 percent in 1992. But there was also good economic news: Hansapank, the flagship of the Estonian economy, was founded and the Estonian kroon was introduced before Midsummer Day.

Since the economic model had changed and business was evolving, financial accounting also had to change. In the Soviet Union, the main task of accounting had been to monitor the implementation of the country’s economic plans and to ensure the protection of socialist assets, but now it was necessary to put the reports to more practical use: to give managers information for decision-making and to serve as a practical source of information for other readers interested in the performance of the company.

The first step in the modernisation of the Estonian accounting and reporting system was taken in 1991 when the charter of accountants entered into force. There were a number of changes compared to the Soviet system: for example, accounting changed from cash-based to accrual-based, and each accounting entity had to develop its own internal accounting rules. The charter of accountants was the guiding principle in the financial accounting of Estonian organisations until 1 January 1995, when the Accounting Act entered into force.

The field of auditing also changed with the times: in 1990, the Board of Auditors was established at the Ministry of Finance as the developer of the field, and the government of the Estonian SSR adopted the Provisional Statutes of Audit Activities. However, it took another four years to complete the first set of audit guidelines. Before this, international audit firms managed to start operating in Estonia: KPMG and PricewaterhouseCoopers were the first to open their doors here in 1992.